ARM, the company that designs the chips in most consumer electronics, is using a new platform called DynamIQ. The processor design of chips like this can tell us a lot about productivity, priorities, and what it means to be human.

Computers have come a long way in the past fifty years. From predominantly professionally used devices, requiring coding skills and a great deal of patience, they are now present in almost every electronic device you use today. Even lightbulbs can contain computers (like digitally controlled Philips HUE bulbs). Smartphone chips in particular evolve in leaps and bounds. In two years your phone is irrelevant. We have leapfrogged from 2G to 3G, 4G and 5G. There are some parts of England where it will take a day to download a movie, and others where it will take a second.

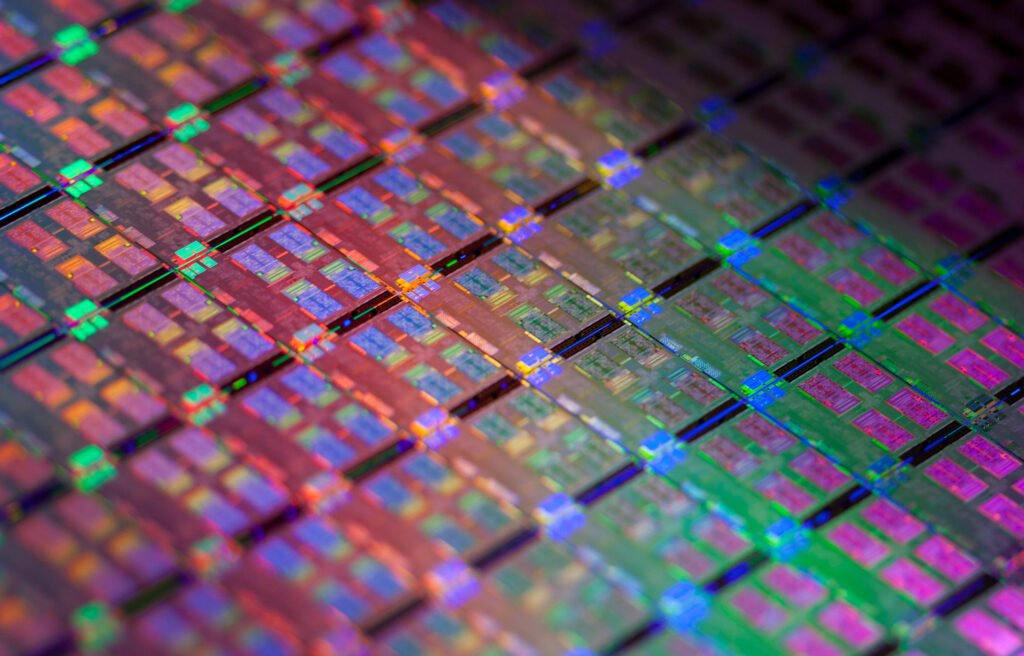

But what makes DynamIQ special is the multi-layered integration of its cores. It uses a hierarchical structure to combine performance with efficiency. Whereas previously, computing cores had to be treated separately by the circuitry, they can now be integrated more closely into DSUs, allowing greater connectivity and shorter distances for electrical currents and information to travel.

What is interesting about DynamIQ is that it does not promise brute force improvements to performance. ARM has not made smartphone computing better by throwing in more transistors, more cores, more memory. What I call physical scaling such as this does occur. One side of the coin of generational improvement is this kind of gradual expansion of determinate qualities, as the processors themselves get evermore complex. But the other, and often most neglected side is what you might call adaptive scaling.

Adaptive scaping involves incremental changes in performance through small, subtle, and often unnoticeable improvements. These kinds of improvements are less marketable. They don’t offer headline figures or easy-to-digest numbers. They focus on efficiency and intelligent design instead.

These are the sorts of changes we should aim to make in our lives. We should aim to do the same things, but a bit better each time. Like the decrease in size of lithography processes from 7 to 5nm or 5 to 3nm, the goals we should set for ourselves would be better focused on attritional innovation rather than big or bold revolution. Revolution sells, but it’s unpredictable, unstable. If you have a genuine commitment to improving life quality, you will eschew the conversational merit of work/life balance experiments. You’ll focus on quiet, but measurable gains.

The architecture of DynamIQ processors themselves are a hierarchical wonder. There are at least five levels of memory. The lowest levels, consumers are more familiar with: the storage which keeps data permanently (usually 16-256GB), and RAM which keeps data temporarily (usually 2-8GB). But closer to the processor itself there is also cache. Cache stores data temporarily but is much, much better integrated with the processing unit. This allows extremely quick access to its contents, so the processor can perform operations without having to access the slower RAM or permanent storage. The issue with cache is that it comes in small quantities, measured in megabytes (MB). Memory at this speed is thus a very rare commodity.

Our minds work like this too. There are select memories which we have easy access to. Our partner’s birthday (hopefully), our address and phone number, the name of our best friend. Then there are things stored in our permanent memory. Information we studied in our degree (again, hopefully), the place where we grew up, the sound of our favourite song. Some of these things are a little harder to access, and we need prompts or reminders to remember all the details. This part of our mind operates like permanent storage in phones, only, it doesn’t feel like it. We don’t have an automatic and natural awareness of our own cognitive structure.

But we should. There is a lot to be learned from this multi-tiered processing setup. We can only store a very small amount of data (some people say seven things) in our working memory, but it is really, really valuable for performing everyday tasks. If we capitalise on the rare/fast and common/slow binary correctly, those tasks can be performed much more efficiently. ARM processors typically use big.LITTLE structures where few big cores complement many smaller cores. Given that cognitive energy is a limited commodity, it makes sense to apportion our day into higher and lower energy segments. Some tasks we do not need to be completely switched on for, so we should do them when tired at the beginning or end of the day. Others require short bursts of intense concentration, and are best placed in what we know to be our highest energy times. It goes without saying that the particulars will depend on the individual, and you need to know your own circadian rhythms to discover what will be right for you. But the structure is the same. No human can be high energy all the time. Thus, we should treat focus like a rare commodity.

There are many, many tasks we do throughout the day which our brain is essentially useless for. As anthropologist David Graeber said in Bullshit Jobs, there is a whole sector of the economy which is committed to ultimately meaningless tasks. It may even comprise a majority. These are the kind of tasks that you get into trouble for for not doing, yet seem to swallow up your day. They take time away from the rewarding things that make up the reasons why you do what you do. But often, they can’t be avoided. These are the tasks we should not use our cache for. We should give them our smaller cores.

Amidst a paradigm of biomimicry and nature-inspired engineering, it may seem strange to take inspiration from the very technologies we control. There is something to be said for the blind awe and deference that the worship of planetary wonder connotes. It makes us less selfish. But sometimes, humans are simple. Fixed laws govern us all. We can live to a hundred if we’re lucky. About a third of the planet has a period once a month. People need to eat and drink and have fun, otherwise they get miserable. Novelty and variety helps, and lockdown proves that thesis. There is also a law of human energy. We can make ourselves generationally better via physical scaling – helping our kids know more, think more, see more. But adaptive scaling requires us to think carefully about what we want to improve. What we want to value. If we don’t, we are living our lives by brute force.